Jake Perry relives the unforgettable nights when Wolves stunned European football and lit the spark for a new era.

On the night of Monday, 13 December 1954, the most significant match in the history of European football was played. Few gave Wolves much of a chance against Honvéd, fielding four of the five-strong forward line that had taken Hungary to 6-3 and 7-1 victories over England in recent months: Stan Cullis’s men, however, had other ideas. Their thrilling win, coming back from two goals down, not only restored the nation’s battered pride but had major consequences for the wider game as well. ‘Champions of the world’, the newspapers called them: a new era of European competition was about to begin.

The stories of Wolves in the 50s are as legendary as the names of the men that wrote them. Three league titles – there could easily have been a couple more – bookended by a brace of FA Cups in 1949 and 1960 represents the most successful period of the club’s history, a run of trophies we can perhaps only dream of ever seeing again. But it was the story of the team’s success on a different stage that really fired my imagination. The floodlit friendlies – that night against Honvéd amongst them – always had a special kind of draw.

My new book, Nights in Gold Satin: When Wolverhampton Wanderers Ruled the World, tells the story of the 16 floodlit friendlies Wolves played at Molineux between 1953 and ’62, as well as other, less familiar, fixtures too: their first match under lights, at Whaddon Road, Cheltenham, in October 1951, for example, a game that played a crucial role in the club’s decision to invest in floodlights themselves, or the first floodlit Black Country derby – not the famous 4-4 draw in the Charity Shield in 1954, but a meeting at the Cross Keys, home of Hednesford Town, in March ’53, a match Wolves won 4-2. But it was the stories behind the games I found most fascinating to explore: the details that add the extra colour to the matches, both well-known and hardly at all.

Take the visit of Moscow Spartak, for example, in November ’54, a match quickly overshadowed by what would shortly come. But this, at the height of the Cold War, was a hugely important game that the whole country eagerly followed, taking in every detail of the Soviets’ time in England as reported in the national press: their dress – ‘among the strange assortment of luggage brought by the players were boxes marked “fur coats”’, marvelled the Express & Star – and training habits drew plenty of comment; even their breakfast order was meticulously noted down (smoked salmon, fruit juice, boiled eggs and steak, ‘and, for those extra carbohydrates,’ the papers revealed, ‘each player had a pot of fresh cream’). ‘To see people coming from behind the Iron Curtain, it was like seeing people from the moon,’ Wolves fan Bob Bannister recalled: ‘Almost impossible.’

Countless hours at the Wolves Museum spent poring over the minutes of the club’s board meetings yielded further insights, too: into the ins and outs of the negotiations to bring Honvéd to Molineux, for example – the match against Maccabi Tel Aviv (which Wolves would win 10-0) was very nearly sacrificed as a common date was sought – and the television deals that were struck (the BBC paid Wolves £225 to televise the second half of the Spartak game but, driven by the arrival of ITV, shelled out £1,000 to show their meeting with Moscow Dynamo a year later, giving the club its first four-figure broadcast deal).

There were also the games that weren’t played. The floodlit friendly against Athletic Club de Bilbao was cancelled as a consequence of a pay dispute between the Players’ Union and the Football League – much to Stan Cullis’s annoyance – but a match against AC Milan, scheduled for 16 November 1955, also fell through at the eleventh hour: though all the arrangements had been made, down to the awarding of television rights, the Italians withdrew after international call-ups depleted their available squad the week before.

I have also looked to bust a myth or two along the way. Wolves’ famous reflective rayon shirts, for example, for many the symbol of the floodlit friendlies, weren’t designed specifically for them: they had been worn for the first time in November 1951, on a dull winter’s afternoon against Charlton in the league. They soon found their place as Wolves’ night-time kit, however, appearing for the first time under lights in a friendly at the Revo Electric Ground at Tividale in February 1952 (more than a year before Molineux’s lights were first switched on) before being worn in almost all the club’s subsequent floodlit matches up to and including the game against Real Madrid in October 1957. I was lucky enough to interview Brian Punter, who wore a prototype version of the shirt (quite possibly the example now on display in the Wolves Museum) in a youth match at the Revo against Birmingham County FA: ‘There was just one shirt, which I wore because I was a winger and the manager wanted to see how it looked from the other side of the pitch,’ he told me. That game brought Wolves a bonus, too, in the form of forward Bobby Mason, who Cullis spotted playing for the county side. ‘Not long after,’ said Brian, ‘it might only have been a couple of weeks, he signed for the Wolves.’ Mason’s 173 appearances for the club would include five in floodlit friendlies: he was amongst the scorers in the 5-5 draw with Dinamo Tbilisi in November 1960.

The book also discusses the legacy of the games: as the catalyst for the European Cup, of course, which began in 1955, and for the club as well. I spoke to John Richards, Kenny Hibbitt and Mel Eves, three of the players I grew up watching from the South Bank, to get their perspective on the burden of expectation the Cullis years left behind. And, for John, Kenny and Jim McCalliog, to take the club on its best-ever European run, too: to the final of the UEFA Cup in 1972.

‘It was the period of the club’s history that established its reputation,’ John told me at the start of our conversation. ‘The team of the 50s was the one that set the standard, and the fans expected every subsequent Wolves team to reach those heights again. We could feel that sense of expectation, that we want this and we’re here to make you do it: it was wonderful in one respect, but quite a lot to carry on our shoulders as well. And we still had some of those players around: Billy Wright, Bert Williams, Johnny Hancocks, Jimmy Mullen, they were all still there and coming to the matches. The history makers.

‘So we definitely felt the pressure from what they’d achieved, but we benefited from it as well. The name of Wolverhampton Wanderers was world-renowned because of that team, and it still is. You go anywhere in the world where people follow football, and they’ll know Wolves. Peter Broadbent, Bill Slater, Ron Flowers: the names just trip off the tongue.’

They still do today. While many clubs can point to their league titles and cups – some to their European silverware, too – only Wolves can call themselves pioneers, the team that ‘lit the spark,’ as the inscription on Luke Perry’s fine commemorative sculpture outside Molineux reads, ‘that ignited European club competition.’ Those were the days, my friend: when our club broke new ground.

When we were champions of the world.

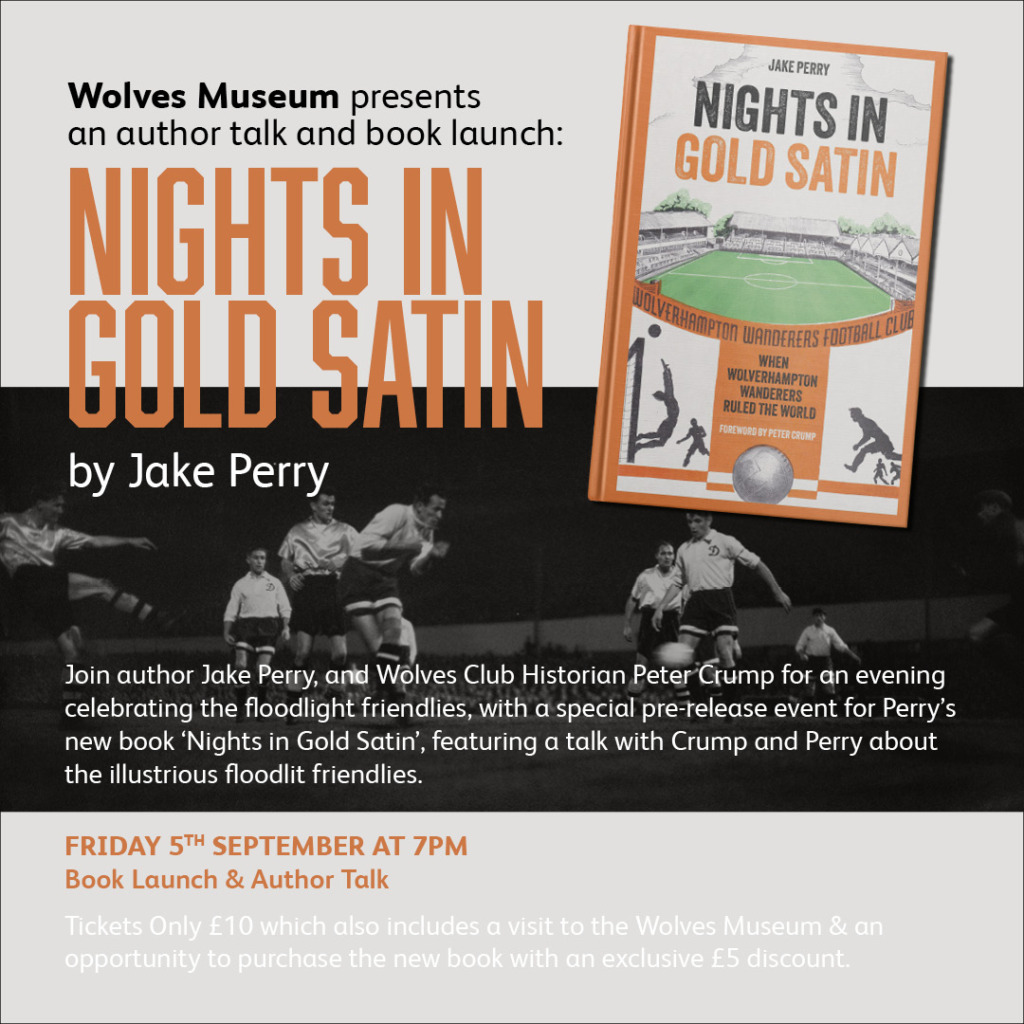

Nights in Gold Satin: When Wolverhampton Wanderers Ruled the World will be launched at a special event at Wolves Museum on 5 September: tickets are available at https://events.wolves.co.uk/molineux-stadium-tours/wolves-presents/

Further information on the book, including pre-orders, can be found at https://www.pitchpublishing.co.uk/shop/nights-gold-satin